As Caregiver for a Beloved, Protect Your Precious Heart

By the front door, a still-frozen, winter window box half-filled with spring for Jack, to cheer coming and going

My husband, Jack, was diagnosed with cancer just before Christmas, upending our world—and my heart transplant discipline. New to being sick with anything, Jack was deeply shaken. Oh, he had faced and reconciled his own mortality before as the leader of a mountaineering expedition in Argentina, but a cancer diagnosis in one’s later years is different. It is somehow more tangible. When I was waiting for a heart transplant at 56 and my father was seriously ill at 89 we talked carefully around the difference, which was that youth put time on my side. Approaching 80 and for the first time in his life, my mountain man questioned his undeniable physical and mental strength. But he worried most about his ability to care for me as he has devotedly since my first heart attack in 1997.

During the first two weeks of shock and action I was physically frozen with terror while also mentally in high gear to save and calm my husband. In my all-out focus on Jack, I unwittingly took my drugs at odd times, neglected daily stretches and exercise, and lost my appetite. Furthermore, there I was during the height of contagion season: an immune-suppressed patient living between MGH and the hotel next door as Jack was being tested and eventually diagnosed. Everywhere people were sniffling and coughing. Back at home I became further depleted while desperately taking care of Jack and assuming his chores. I immediately caught a cold and my neck knotted for the duration. Adding to our stress, the winter of 2018 brought a parade of record-breaking nor’easters, heavy snow and strong winds creating a nightmarish three-hour commute to chemo sessions from our small town in western Maine to Mass General Hospital in Boston and back, every three weeks. It was hard. And it was just life doing what life does with no exceptions.

If you are lucky enough to be alive with a heart transplant or another chronic condition, then you certainly know that life does not stop its flow for you. Though fragile yourself, people you love may become seriously ill or face other crises and need your devoted care. Meanwhile, other responsibilities need attention, nourishing meals need to be prepared, and bills need to be paid. In other words, the basics of normal adult life must somehow go on at the same time that your beloved and you are in total crisis. The experience is overwhelming—even for those of us skilled in problem-solving and multi-tasking. Despite your feelings, whether the crisis passes in a day or continues for years, you cannot become overwhelmed. You must be clear-headed and strong; you are needed and necessary.

Jack and I had a surprising advantage going for us during the winter of 2018, however. The dark gift of my 21 years of cardiac crises dawned on me one day as we glumly picked our way along a snow-piled Charles Street to lunch somewhere, anywhere, outside of the hospital. I was doing my best to center my progress, inside and out, when a barely formed thought escaped into audible words

“You know? Other people’s lives would be devastated by this cancer news.” Jack stared at me as though I had suddenly grown horns through my thick wool hat. “But I am devastated, Deborah. Aren’t you?” Oh, dear, did I say that out loud?

“What I mean is, if you think about it, here we are on Charles Street—again—deciding where to eat lunch. Nothing has really changed in our lives. For 21 years, it has been our frequent routine to drive to Boston for my medical junk. We go to multiple appointments and procedures, we get good and dreadful reports, we stay in a familiar hotel, we sit in waiting rooms. I am hospitalized and you sit by my bed. Now I sit by your bed. We always figure it out.”

Jack still wasn’t with me, so I pressed on. “My point is, we are experienced at this. Others have no idea how to cope because it is all new. They don’t even know where to grab a bite to eat and fresh air between appointments.”

Jack was quiet for a minute, and then we shared the oddest laugh at what I guess you could call our good fortune. Cancer, too, is life and we know how to cope.

It was the nascent cold that forced a reckoning with my challenges as a caregiver. During my worst cardiac years, Jack had been in peak physical condition as my devoted caregiver. Now in his time of need, my body was compromised and unreliable, as is the case with any transplant recipient. My well-being depends on adhering to multiple medical protocols and disciplines, many of them daily. Also, being immune-suppressed I am vulnerable to infections. If my little cold developed into the annual, full-blown bronchial/pre-pneumonial mess, not only would I be too weak to help Jack, I could infect my cancer patient and add to his risk as he headed into chemo, already a weakener of the immune system. Thus, my first priority was to vanquish the cold before it developed. This was hard for me, mainly because I had to make my health needs equal to Jack’s during his crisis, or we would both be lost.

I grabbed onto my usual solution for being overwhelmed by channeling my stress into organization, right from the hospital. I called and emailed around and cleared our lives of all energy drains and distractions. I asked people to send Jack snail-mail notes and not to email me so I could focus my energy on the patient; I promised to send e-bulletins of progress from time to time. At home, I moved into a guest bedroom to protect Jack from infection. I slept and hydrated aggressively. For the return to MGH I packed Mucinex, extra hand-sanitizer, tea, broth, thermoses, and requested a portable water boiler from the hotel. Every day at MGH, there I was beside Jack, wearing my customary mask and carting around two or three thermoses of hot tea or broth. I slept where I sat, mask on. After Jack had drowsily settled into his first chemotherapy session (lasting seven hours) I escaped to the hotel to grab a good nap and refill my thermoses for the return to MGH. Jack never caught my cold and I managed to beat it for the first time in the 12 years since my heart transplant. I suspect pure warrior determination helped.

Thus began a continuing effort to find my balance between Jack-care and self-care, a discipline that heart transplant graduates ignore at their peril. Now six months and six chemo sessions later, my beloved is in total remission. He may be skinny and bald, but he is all here and gaining strength every day while sitting by the lake in the summer sun. The healing and rebuilding have begun. That goes for both of us.

Intensive care for beloveds, from children to elders, may go on for years, made more complicated if the caregiver is managing her own chronic illness, especially if compounded by being immune-suppressed. At MGH, I meet many colossally strong heart transplant patients, many of whom have beloveds depending on their daily care and attention, often children and elders. The husband of one couple I met received a heart transplant a few years ago when their young son was also on the waiting list for a new heart! I am in awe of all of you. To be both patient and caregiver at the same time has been one of my biggest challenges in Cardiac Land.

The recommendations below reflect my experience, as well as what I learned from Jack as my caregiver while keeping himself well and strong over the the last 21 years of our complex lives. The winter of 2018 was my turn to wear his outsized caregiver shoes, an experience that has increased my respect and love for him and for all caregivers—the best of whom know that taking care of your self is not selfish but the responsible thing to do for all your beloveds.

- Place the oxygen mask over your own face before attempting to assist others. After fastening your seatbelt, you hear this announcement before every flight takes off. Self-care is critical to cardiac patients during a crisis or you risk the well-being of your beloved-in-need. Set yourself up to be able to take your meds on time, no matter where you are. Make time to eat properly, including fruit, vegetables, and healthful protein. Hydrate, hydrate, hydrate; the air in sealed buildings (hospitals) is inherently desiccating. Do your stretches, anywhere. Keep up your cardio-exercise by slipping it in throughout the day. Even a few minutes makes a difference; for example, jump around in a waiting room and use the hospital stairs rather than the elevator. Center yourself and lower your stress by simply breathing. I find it remarkably calming and re-energizing to close my eyes—in a crowded waiting room or in a check-out line—while taking three deep, gentle inhalations through the nose and exhalations through the mouth. No one ever notices and I am renewed when I open my eyes. And, finally, need I remind you to wear a mask whenever you are in a medical building? Every medical office is a petri-dish of germs. If you get sick, you are a danger to your beloved.

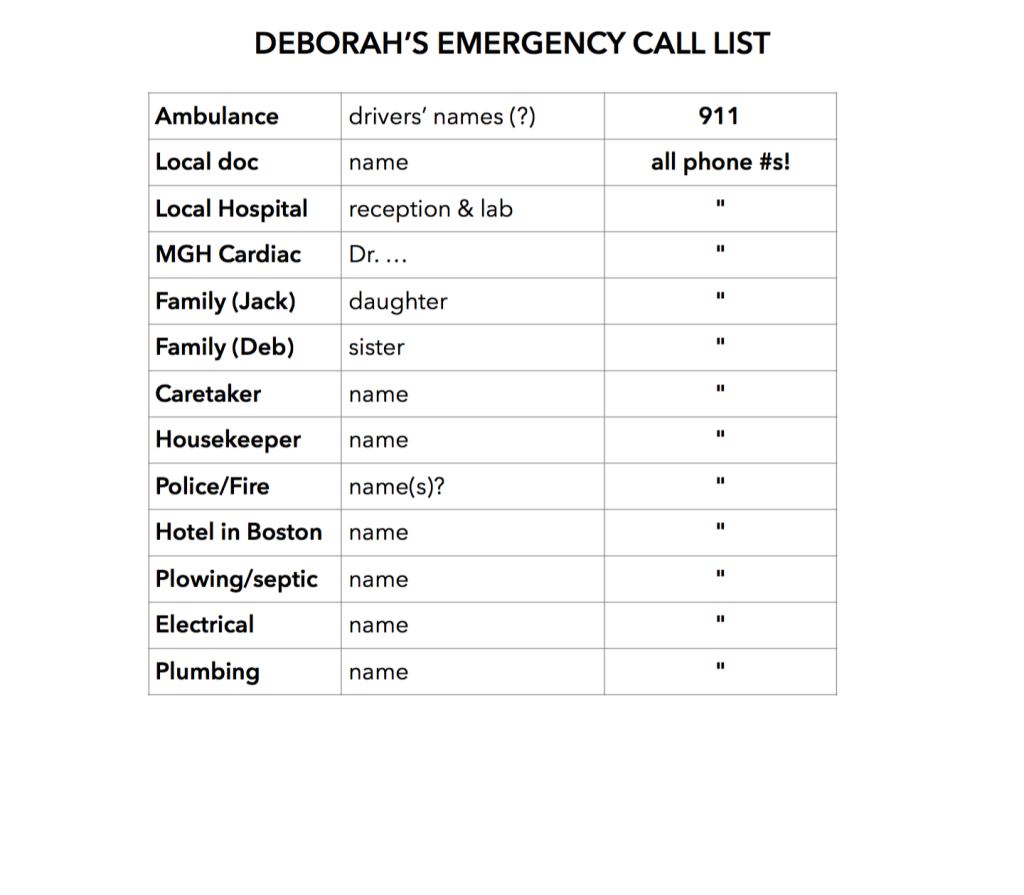

- Get Organized. I followed my own instructions to create for Jack his own Medical Notebook. (See Tips & Tools on this website.) It began with a pad of paper I grabbed when our primary care physician called with Jack’s terrible CT results. I wrote down every word she said to make sense of later;I did not know which words were important, many of them new to me. I kept all our initial notes and data on that pad until we understood more. At every appointment, I scribbled notes so Jack could concentrate fully. Once we knew his diagnosis and treatment plan, I transferred those notes to a three-ring binder with dividers, tailoring my website instructions to meet the needs of a cancer patient. Having one place to keep every bit of vital information calmed and readied Jack. It helped his head to stop spinning. As his cancer experience developed, we were prepared participants in every meeting with his clinicians. They were impressed; many patients remain in panic mode and retain little information largely because they do not write it down. Jack’s stress level and mine lowered because we felt we had some control over our response to and management of the crisis.

- Simplify. Delegate. Postpone. Cancel. Communicate. What tasks can you get rid of right now? De-clutter your life quickly. Everyone will understand. Just do it. Clear your head and your schedule so you can focus on your patient and others who truly need you, as well as on your own self-care. Ask for help and understanding. People like to help, to feel useful when someone is struggling. Asking will widen the circle of love that you and your beloved need for getting through this. To address people’s concern, consider periodically sending an email with progress updates. Following my first shocking heart attack and again following the heart transplant, Jack fielded hundreds of calls from concerned people. He found that speaking with everyone was a good outlet for his own emotions. As soon as Jack got sick, I recognized my health limitations and knew that talking with so many people would drain energy that I needed to harness for Jack and my own well-being. So I sent to family and friends a thoroughly informative group-email at three key points in the chemo process and gave them permission to forward our “report from the front” to others. It ended up being a terrific idea, keeping everyone involved and informed and avoiding hurt feelings of being left out. Furthermore, when I ran into friends and acquaintances at the grocery store, I didn’t have to keep repeating the story, releasing me for a moment from the nightmare we were living. Jack’s son dubbed my emails The Winter Cruise news because one dreary day I had proposed to Jack that we name this time in our lives the Winter Cruise, since we live isolated on a peninsula surrounded by ice. Jack loved it; a Winter Cruise was an expedition he could handle. Friends adopted it, too, asking “How’s the Winter Cruise going?” instead of using the “C” word. Whatever works!

- Surround yourself with love; your health depends on it. Who gives you energy? Who takes it from you? Who is calming and loving; who is needy or cyclonic? Trim your life of all drama during a health crisis to make room only for people who make you feel happy, understood, supported, peaceful. When Jack and I have felt someone tugging us off balance from the centered focus we have needed during crises, we have done our best to practice letting go with compassion. Some relationships may just need to be paused during difficult times because your reality and needs come first. Perhaps philosopher-theologian Reinhold Niebuhr’s prayer will help you as it has helped us: “Grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, the courage to change the things I can, and the wisdom to know the difference.”

- Post-crisis: Rest deeply and for as long as you need. Especially if you have a condition as complicated and precious as a heart transplant to protect, when a beloved becomes critically ill, you, too, in a sense become “ill.” Cardiac and transplant patients often acquire deep empathy for others, a gift of our own suffering. We cannot help but feel everything the beloved is enduring and suffer right along with them. I know this is true of me. So, while your beloved recovers, I suspect that you will need recovery time, too. Sleep and rest as much as you can. Resist immediately re-loading yourself with activities and obligations that you put on pause for the duration. You are not fully yourself yet. First resume healthful routines that you may have had to forgo or shorten, such as massage and your full work-out routine. Be sure your own medical appointments continue, some of which you may have had to cancel during the crisis. Give yourself space and time to let the stress dissipate when it is good and ready to exit your body, mind, and spirit. Pay attention to that moment and give it release. Scream, cry your eyes out, dance like a fury! Purge it so it does not damage your health. Your clinicians worked hard to give you life. And your donor made this life possible, which includes both joy and suffering. So take care of your big, loving heart, the little pump that makes both dancing and coping with disaster possible.

This summer of recovery, Jack and I are both deeply tired, sleeping at least 10 hours a day and feeling no guilt. Remember this: Hope is work. It takes vision, focus, determination, faith, discipline, and kindness. And when you no longer need to harness so much hope, you will be physically exhausted by your mental and spiritual marathon.

Now at night, I can feel warm vigor returning to Jack’s body close beside me, in contrast to the icicle he was until sometime in June, despite sleeping in his “monk outfit”: a fleece pulled over his long, flannel nightshirt, finished with wool socks, hat, and scarf. Now, every Saturday at the farmers market, our social outing of the week, people are happy to find us radiant as Jack makes weekly gains in strength and vitality. He is rocking the bald look, which everyone hopes he’ll keep, even if his hair is beginning to grow again.

Despite all my efforts at organization and competence, two weeks ago I woke one morning feeling leaden. I could barely lift a limb and my mouth just would not turn up in the smallest smile. I was deeply depressed, despite the gorgeous summer day and every reason to be joyful and grateful. And then I recognized what was going on. The grief and terror that I had tucked away in the deep recesses of my being were moving out and into my body for physical release. I had experienced this process before and recognized a form of PTSD. Because Jack was safe and on the mend, I finally could give into forces that I had been keeping at bay to cope, to get the two of us and other beloveds through the crises. I cried my eyes out, curled in fetal position, then fell asleep for several hours. As the sun began to set, I woke to Jack rubbing my back, offering a glass of wine and an invitation to go outside and watch the greatest show on earth. The morning’s weight was gone. Instead, I felt light, triumphant. We had done it! My husband lives. And now so can I.

END